Dear friends,

As of August 15th, I am officially a Peace Corps Volunteer! We had a beautiful swearing-in ceremony (photos below). That means I have now moved to a new village, where I will be for the next two years. And it means that I have said “see you later” to Bardar, the village where I lived and trained for two and a half months. Today I’d like to share a story of one Sunday afternoon from July to try and convey a little bit of what what Bardar was like.

First, a round-up of recent life happenings:

Topped off 165 hours of Romanian language lessons

Spent a day as a tourist in Chișinău (the capital) and visited: the national cathedral, the national art museum, an Uzbek restaurant, the central market, and (my favorite) the national cemetery

Organized a community clean-up event at the local sports field as part of our practicum training. We worked with the local youth council to identify the need and the mayor’s office to provide larger trash cans, so that future pick-ups are less needed. After the clean-up, we played an educational game about trash then spent a few hours enjoying the space

Had a great dinner with one of the host dads. Domnul Gheorghe invited all nine of us from Bardar. He told us about the 4 or 5 countries he’s lived in, his family, and his thoughts on renewable energy (he thinks nuclear is too dangerous)

Collected potatoes with my host mom and Ted (fellow volunteer)

Visited a local monastery for Sunday services, Sf. Nicolae at Condrița village

Helped to host a potluck with the other Bardar volunteers to thank our host families for a great start to our Peace Corps journey

A Tale of Three Hosts

Sunday, July 27th, 2025

At the start of the day, I don’t have any special plans. Most of the other volunteers are going to a neighboring village, Vasieni, for their Village Day, but I want to take it easy. Last weekend I went to explore Chișinău and next weekend we have our community events. I wake up and am ready to walk to church by 7:50. Ted and I arrive during the Hours between Matins and Liturgy. Buy our candles in the narthex, venerate the icons in the front, find spots to stand. Today we stand next to Dna Tamara, one of our neighbors.

Later, during the priest’s communion, I notice that Oleg has slipped in and is standing just behind me. I met Oleg last night. The youth council had organized a “discotecă” (picture a high school dance, sans chaperones) at the Casă de Cultură. I won’t lie, I was a bit out of my element - both with the throngs of boys outside by their motorcycles and the clusters of girls indoors. It was easier for me to walk over to the small group of boys talking next to the sound equipment, one of whom was Oleg. I had a hunch that at least one or two of them were on the event committee. More my speed. Once I got talking with them, they were able to introduce me to the guys outside, and together we were able to convince some of them to dance inside with the girls.

It’s noteworthy that Oleg is at church today because he’s one of the few young people that I’ve seen at Liturgy. After service, he comes over to Ted and I, saying, “Today is my birthday. Would you like to drink a beer with me?” Absolutely.

We exit the church building and stand in the courtyard, where the church ladies serve us a snack of stuffed cabbage rolls on sliced bread. Dna Tamara comes up and invites Ted and I to her house for tea in the evening. And I remember that on Friday, someone else invited me to swing by his house on Sunday evening. I can do that between Oleg and Dna Tamara. And with that, my Sunday is suddenly full.

Oleg

Oleg, Ted, and I walk down the hill from the church to the closest convenience store. When I take out my wallet to pay for the beer, Oleg stops me. “It’s my birthday, my treat.”1 He takes us to an enclosed patio behind the shop that I don’t think I could have found by myself, where we sit a few tables down from a group of middle-aged men smoking and drinking. We talk in English, since Oleg’s skills far surpass our Romanian.

Oleg is 19 years old and just graduated from the high school here in Bardar. He remembers seeing us at the ceremony, which Ted and I attended because our host granddaughter was also graduating. He’s not sure exactly what the future holds for him. He originally was thinking of joining the navy in Romania but decided against it. He also considered applying to university further abroad, perhaps in England where his father lives. Ultimately he applied to schools in Moldova and Romania, to study international relations and/or computer science.

I discover that my hunch was right about the boys by the sound board. Not only is Oleg a member of the town youth council (and the only male member who was able to come last night); he also was the president of the student council. Oleg says that being president was great because everyone looked up to him and he felt a lot of pride for the community.

Oleg mentions that he works a small job to make money but that his biggest responsibility is caring for his two younger brothers, especially since his dad is abroad. When his mother or grandmother are busy, Oleg helps to prepare food or walk them to where they need to go. He’s worked in construction and as a waiter. He remarks that he feels bad taking money from his mother because he’s old enough now to not do that.

For his birthday, Oleg’s friends surprised him last night by coming over to his house. He shows Ted and I the video of his friends splashing a bucket of water on his face, followed quickly by a cake. “I couldn’t see anything!” he laughs. Tonight, he will host a barbeque in the forest with his friends. He graciously invites us but I’m going to Dna Tamara and Ted is going to Vasieni’s festival.

After finishing our beers, Oleg walks Ted and I back to our house. We will see each other again soon, at least at the community clean-up event.

Vasile

In my second letter (from July 1), I mentioned a man who briefly met me in front of the school. Well, two days ago, Dl Vasile came up to me again. He was waiting for me on the front steps, as I rushed up at 7:59 am.

“I have a collection of old icons in my cellar. I thought you might like to see them. And there’s also other old things. You can come any time during the evening on Saturday or Sunday. Write down my phone number, and just call me when you get close to my house.”

Today, after Oleg walks us home, Ted and I eat lunch with our host mom, Dna Maria, before he heads to Vasieni. While eating, I tell her about my plan to visit Dl Vasile and his icons. “Ah, Vasile Pisica! Yes, he is responsible for the grounds and maintenance at the school. I know about the old icons. A TV reporter came and filmed a story about them.” This is surprising.

“But how are you getting there?” “I’ll walk.” “Oh no, don’t do that. We can drive you.” I briefly try to protest, but Dna Maria insists, and she adds that her daughter’s family is nearby. I figure I’ll accept the ride if it means that Dl Vladimir and Dna Maria can visit their granddaughter while I’m with Dl Vasile.

When we arrive, Dl Vasile invites my host parents to come inside with me. After a few polite protests, Dna Maria gives in, saying that she’s not seen the collection yet. Dl Vladimir stays in the car.

As soon as we descend the few steps down into the cellar, my first impression is a wall of color. I’m looking at a room with every inch of wall space covered by icons or photographs. It’s a lot to take in. Dl Vasile starts pointing out where he got the icons and who they depict, speaking more quickly than I can process. I hear Ukraine, Russia, Romania, Germany. Some were going to be trash before he took them. Were gifts from monks. Previously hung in public buildings. Purchased on vacation.

But the thing that sticks out to me the most here isn’t actually one of the icons, though they are all beautiful. It’s the little table with clear signs that this is not just a museum - this is where he comes to pray. I spot printed lists of names “for the living” and “for the dead,” well-worn prayer books, reading glasses, a vase with cut flowers, and a lit candle.

After Dna Maria and I admire the icons, Dl Vasile waves us into the second room, which is filled with the “old things” that he’d mentioned. Again, everything is neatly arranged and tightly packed. He points out old tools, jugs, textiles, lanterns, clocks, a coin collection, and photographs of him with family, friends, and clergy.

Between the two rooms, it’s more than I can appreciate in a short time, and I’m conscious of Dl Vladimir waiting outside. I ask him a few more questions about the people in the photos and the icons, but then we’re up and out. Back in the car, a short drive, a visit with Daniela, and then home for dinner.

Here’s the TV interview: Unde alții țin murături, el ține candele: Povestea beciului lui Vasile Pisica

Tamara

At 7pm, Dna Maria and I wrap up our dinner conversations and I fill up an old plastic bottle with red wine from our cellar before walking over to Dna Tamara’s. We squeeze our way through our back gate then walk for a few yards through overgrown grasses and between large shrubs before arriving at another wooden backyard gate. Just outside the gate is a plum tree, heavy laden with fruit. Dna Maria suggests that we gather a few to bring over. She’s pretty sure the tree belongs to Dna Tamara’s father.

“Tamaraaaa!” Dna Tamara hears my host mom and pops out of her front door with her mother. She invites us to sit under the shade of a large tree in her yard, where a ring of log stumps are neatly topped with colorful crocheted covers.

Dna Tamara is a lively, middle-aged woman with reddish-brown hair. She lives here with her elderly parents. Her parents are more quiet than their daughter, though I think in her father’s case that may be because he’s hard of hearing. He also has a tendency to forget that I don’t know Russian. Dna Tamara ask about my work with the Peace Corps and exchanges town news with Dna Maria before suggesting that we move to their patio table for tea.

As we talk, I keep thinking that Dna Tamara has finished serving us, only for her to duck inside and come out with more. We start with the red wine from Dna Maria before moving onto tea (I choose a red, floral blend). For food, Dna Tamara brings out placinte (hand pies) in three varieties, corn, cookies, and ice cream. No matter that we’ve already eaten dinner.

During our conversations, I learn that Dna Tamara has had a really impressive career. After being a teacher and principal at the school here in Bardar, she moved on to work for the Ministry of Education. Recently, Dna Tamara completed a study about how to improve low test scores for children going into high school. Two of the largest issues are cheating and parents acting as a crutch for their kids during the school year.

Before the night ends, Dna Tamara offers to show me her casă mare, which is a type of room where Moldovan families keep traditional items and host guests, especially for important events like wedding parties (traditionally hosted at home). It’s sort of like the American formal sitting room, which both of my grandparents had in their homes.

In her casă mare, Dna Tamara has covered the walls with hand-embroidered linens and traditional tapestries. She has a few storage chests, pictures of her parents, and two stuffed animals. She laughs, “no, the stuffed lion is not traditional!” One of the embroideries has something written in Russian, or so I thought. “Ah, this is actually Romanian, but using Cyrillic letters, which replaced Latin letters during the Soviet period.” Dna Tamara also points out that her mother’s wedding crown2 is preserved next to an icon of the Virgin Mary. When I ask about what is in the chests, she describes a tradition in which a Moldovan will make towels which are then distributed as gifts to guests at his or her funeral (if I understood correctly).

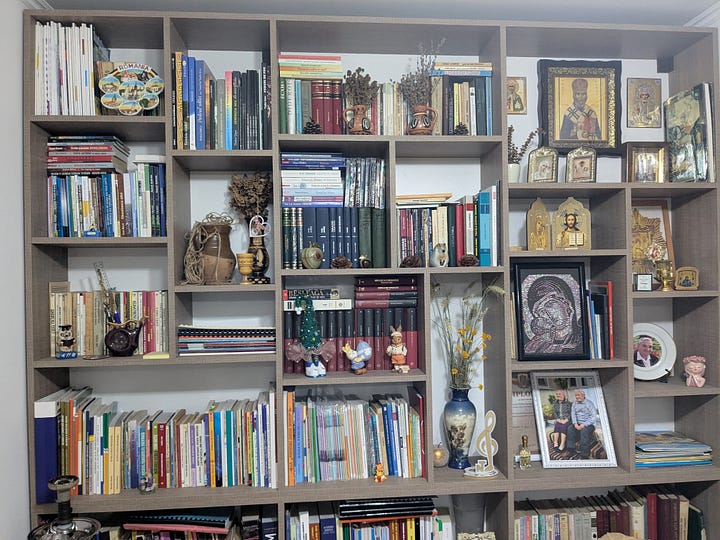

Finally, Dna Tamara shows me her bookshelf. It’s fittingly impressive for a former literature teacher. On a shelf near the bottom, she pulls out a little stack of booklets. “These are exams that I helped develop as part of my work at the Ministry. See my name on the inner cover? Here, take one as a gift.” In blue ink she writes (in Romanian), “For Nathan, with love and respect for the beautiful attitude with respect to the Romanian language. Success! Tamara 2025.”

With love and respect,

Nathan

My views are my own, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Peace Corps, U.S. Government, or Republic of Moldova.

For birthdays in Moldova, it’s customary to bring food to share with your workplace or school. And to prepare all of the food for your party.

After a bit of back and forth confusion, I finally realized that this cununia is not the same crown that’s used in the religious crowning ceremony at the church. Rather, this is a symbolic floral wreath worn throughout the wedding festivities.

this is so lovely! Thank you for sharing :)

lovely story! i hope you had a wonderful first week at site 🫶